The science of enterprise alignment

Could measuring the alignment of organisations – and empowering executives to improve it – hold the key to better corporate productivity?

Words: David Turner

Way back in the 1970s business schools abandoned a hugely important topic that is key to corporate productivity, says Jonathan Trevor, Associate Professor of Management Practice at Saïd Business School: organisational design. Four decades later, he is endeavouring to make business – and academics – think about it again in the context of 21st century business challenges.

‘Organisational design’ – treating every enterprise as a system that needs to be designed effectively – ‘is a critical component of success, but it is often overlooked,’ explains Professor Trevor, who teaches on the Oxford MBA, Executive MBA and international executive education courses.

‘It’s notably absent from many MBA programmes and is not taught in executive education either.’ Academics have neglected the topic out of a false sense that it has been sorted out, he says – a notion that, job done, they can move on to something else. More specifically, he says it is important to measure how aligned enterprises are, whatever their field of business – alignment being the degree to which their purpose, strategy and organisation (through which the enterprise’s work is performed) work together in harmony. ‘A renewed focus’, he says, ‘is potentially a way of dramatically enhancing productivity.‘

Strategy must be aligned with purpose, organisational systems must be aligned with strategy

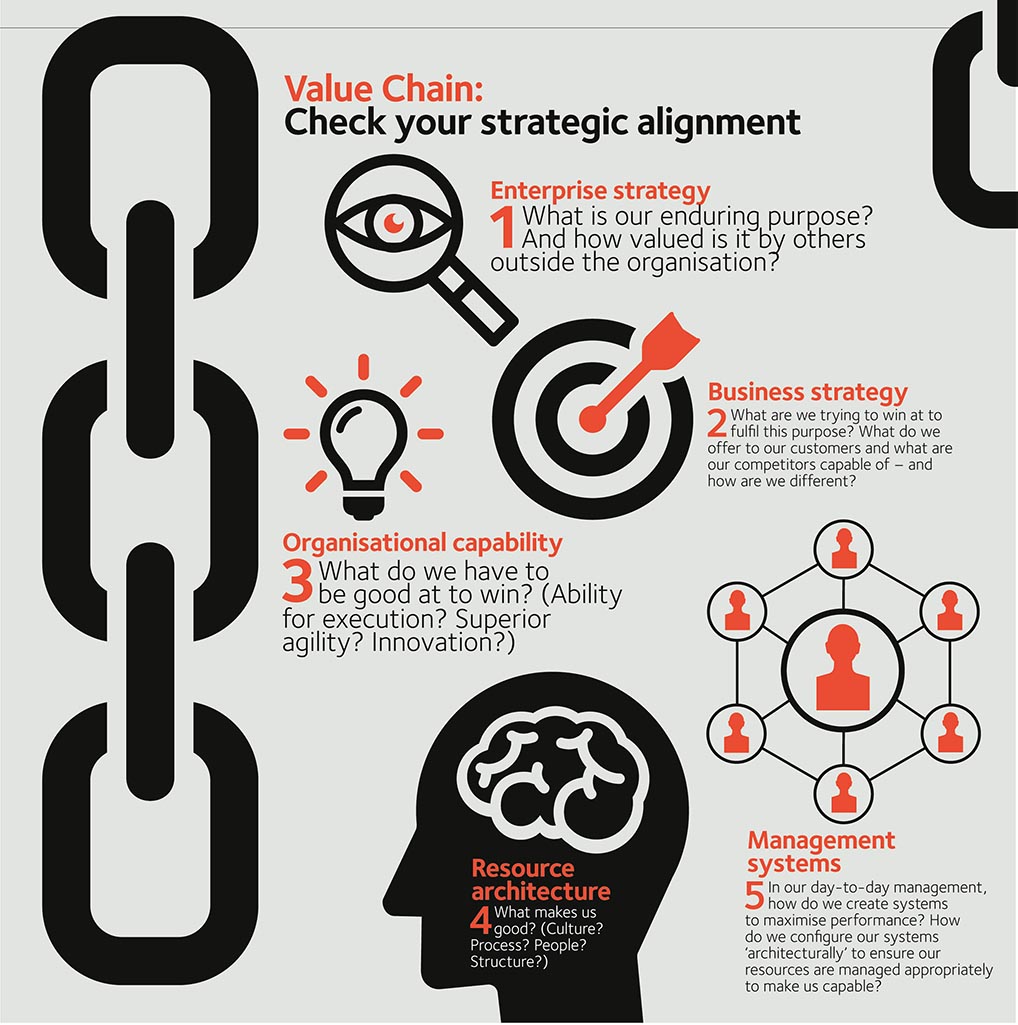

Professor Trevor talks about five components that make up the aligned enterprise, and which are necessary both in commercial organisations and in non-commercial enterprises such as government departments: enterprise purpose, business strategy, organisational capability, resource architecture and management systems. Strategy must be aligned to purpose, organisational capabilities must be aligned to strategy, and so on, if the enterprise is to perform its purpose as effectively as possible and win in the marketplace.

Going into the five components in more detail, Professor Trevor describes the first part of the chain, enterprise purpose – ‘what we do and why we do it’ – as ‘the lodestone for every enterprise’. The second part of the chain, the business strategy designed to fulfil that purpose, ‘must be a strategy aligned with what customers and markets demand’. The third link, organisational capability – ‘what we need to be good at to win’ – is the core set of distinctive and valuable capabilities required to achieve the strategy. Professor Trevor describes it, intriguingly, as ‘the most neglected part of the value chain’. Resource architecture – ‘what makes us good enough to win’ – includes the organisational cultures, structures, people and work processes needed to develop strategically valuable organisational capability. The final part of the chain, management systems – ‘what delivers the winning performance we need’ – includes the information systems, human resource management systems and workplace factors that drive the performance of a company’s resources.

The nature of misalignment

Examples of misalignment are abundant, from which we can learn a lot. He quotes one from personal experience: he did some work for Royal Bank of Scotland in 2008, the year it suffered the largest annual loss of any company in British history

‘In some respects, it was a highly aligned organisation,’ he remembers. ‘If you asked ten people the same question you would get ten similar answers – superficially a sign of alignment.’ He concludes that its resource architecture and management systems were strongly in sync. One area of weakness, however, was its strategy and style of leadership. ‘People used to tell me that the company had a strategy of not having a strategy. If I then asked what they were working for – what was the agenda? – the agenda was “Fred says”,’ says Professor Trevor. He thinks that this command and control approach, based on obeying the orders of Fred Goodwin, the then Chief Executive, was misaligned with the realities of running a complex global financial services organisation.

People used to tell me that RBS had a strategy of not having a strategy. If I then asked what was the agenda? The agenda was “Fred says”

However, the nature of misalignment varies from business to business. Arguably, one of Microsoft’s weaknesses in the first decade of the millennium – manifest in its firm financial performance – was its performance management system. ‘It ranked all its employees and penalised the bottom 10 per cent each year. This put all individuals into competition, but the best way to win strategically was to encourage collaboration among its people.’ In the end Microsoft abandoned this system; GE jettisoned a similar way of doing things. Today, Satya Nadella (the current CEO) runs a very different ship to that of his predecessor.

Challenges of the 21st century

People might ask why, in businesses that are broadly meritocratic, alignment is so difficult. Professor Trevor describes it as ‘harder now than it has ever been’. One answer to this question is that great corporate changes can force a company out of kilter. ‘RBS bit off more than it could chew with its acquisition of ABN Amro in 2007,’ says Professor Trevor. ‘Overnight, it became a more complex organisation to manage, in terms of its culture, resources, size, diversity of business offering and activity.’

Another answer to the question is that buying behaviour has changed drastically – customers want more things than ever before. Professor Trevor says that for much of the 20th century, companies in many industries won by offering value for money, as a host of products were transformed from luxuries of the rich to everyday commodities within reach of the masses.

‘Affordability was the name of the game,’ says Professor Trevor. He quotes the famous oxymoronic pledge attributed to Henry Ford, a genius at pioneering the assembly line production of motor cars in the early part of the century: ‘You can have any colour you want so long as it’s black.’

Affordability was the name of the game: you can have any colour so long as it’s black

Professor Trevor says that this has all changed. These days, customers desire highly personalised products and services that are also well integrated to form a bundle of items worth more than the sum of their parts. A good example is the smartphone – ‘It’s smart because it connects multiple different technologies and provides a platform for users to personalise their phone’s functionality via the application ecosystem.’

Professor Trevor is, however, not pessimistic or defeatist. He can regularly find plenty of examples of alignment.

One of these is Coutts, bankers to Her Majesty the Queen. Whilst part of the RBS Group, Coutts is a good example of a stand-alone business that follows its own path.

‘This is a high-value, low-volume business,’ he says. ‘Each customer relationship is unique to the customer’s needs. They win by offering a personalised suite of financial services.’

But while Coutts is a classic case of the trend towards personalisation, Professor Trevor warns against assuming that all industries work this way. McDonald’s is an interesting inversion of Coutts: he notes that its high-volume, low-margin model requires it to sell as many burgers as cheaply as possible, to a certain quality standard.

Measuring alignment

How can Professor Trevor work out whether a company is aligned? His goal and that of his colleagues at Saïd Business School is to use an evidencebased approach as much as possible. ‘We are delivering a scientific way of better measuring alignment,’ he says. His team goes into each enterprise armed with a set of 16 scales known as the Enterprise Alignment Diagnostic. After gathering relevant data from a variety of different sources, including interviews with key personnel, it uses these scales to create a map of the company, including organisation structure, culture, people and work processes, that can be measured against the ideal for its market. Professor Trevor also has some tips for self-diagnosis (see below).

He gives an example of how something can be measured and then compared: organisational culture. He observes it by talking to people at all levels of the organisation to assess attitudes and perceptions. A closed culture, based on ruthlessly following tried and tested processes, is necessary for what he calls ”an efficiency play“, as in the case of McDonald’s. An open culture, founded on a high degree of personal initiative and questioning, is necessary for ‘an innovation play’, the desired model for Microsoft.

Even when improvement is achieved the management must remain vigilant. The value chain requires constant nurturing and nourishment

Professor Trevor has an answer for the sceptics who question whether companies can improve by focusing consciously on alignment: he has seen his methods work. He gives the example of a market-leading international insurance company, whose interest in the idea sparked his first practical application of his work in this area. ‘I was approached by the insurance company at a conference just after I had spoken about alignment,’ he recalls. ‘They said: “This is great, but we don’t know what we look like.”’ Professor Trevor helped create a “map” of the company, showing how it was aligned – the first step towards improvement. The divisions of the company to which this technique was applied showed progress when judged by a wide range of metrics, including employee engagement, cost control and financial performance. It would be a mistake to think that identifying misalignment has an instantaneous effect, he counsels. ‘It took about a year to begin to work – there’s no silver bullet. It’s not like a piece of technology you can buy, install and immediately see a difference in results from.’ Moreover, even when improvement is achieved, management must remain vigilant: ‘The value chain requires constant nurturing and nourishment.’

Many executives – perhaps most of them – will think that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with their business. If this is the case, why do they need to consider alignment? Professor Trevor’s answer is that any company can improve – even businesses that are leaders in their market. ‘The companies that survive do so because they are “good enough”, and they are good enough because they are aligned to a degree,’ he says. ‘The question is: how much better could they be if they were more aligned, and how much better off could shareholders be if alignment were better?’

And not just shareholders – employees too. The state of an enterprise’s alignment is often obvious just from a first impression. ‘One can see it in the workplace in the way people behave, in the speed with which people walk. In an aligned enterprise, people act with a greater sense of urgency.’ For insiders, one clue is the amount of office politics: ‘Aligned companies experience much less squabbling.’